Michael Brough’s best works are not sprawling simulations that place a universe at your fingertips; nor are they more contained simulations that nonetheless remind you of your place in humanity; nor are they decorated narrative walkabouts. Brough’s best works are cerebral puzzles, untarnished by anything that might deserve to be called extra.

Most importantly, Brough’s best works satisfy the correct definition of “game.”

Before he was known for dynamic, clever short-form games, Brough spent many years toiling over a commercial title called Vertex Dispenser, a wickedly smart real-time strategy game that flaunts geometric art and strict difficulty. Vertex Dispenser is full of depth, imagination and ambition. If this were a site that promoted commercial games, I might say that Vertex Dispenser is criminally under-appreciated because it’s hard (what I’m saying is go buy it).

I bring up Vertex Dispenser because it’s a strategy game with a puzzle nestled inside of it. Brough has written on his blog that he doesn’t like solving puzzles because puzzles are inherently ephemeral and restrictive; you finish them, and then they’re gone. Brough clearly belongs on the designer end of the puzzle equation because he manages to make the player feel as if this isn’t the case. His puzzles are like minimalist paintings of math or architecture that you can tear apart. They are moving, but it’s not always clear why.

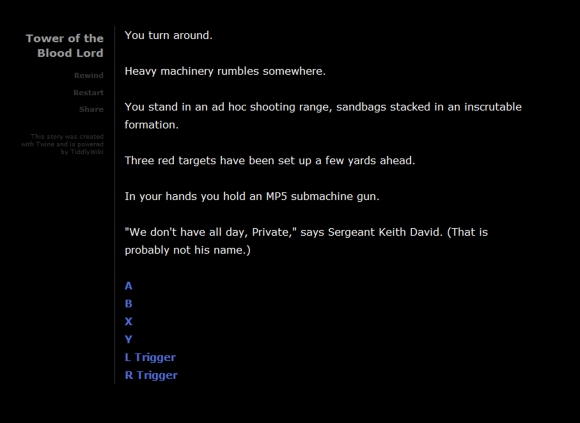

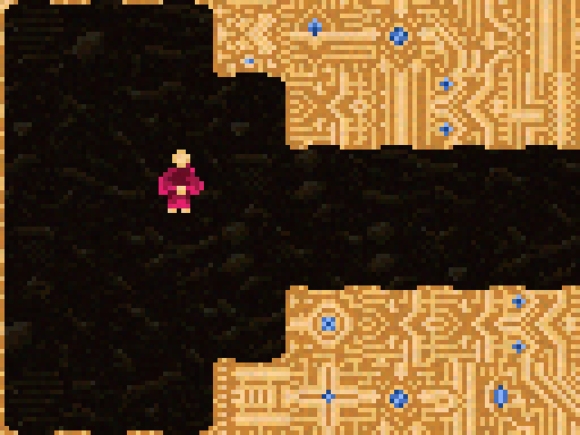

Corrypt is a puzzle that masquerades as something lesser than what it is. As you uncover its secrets, the entire system threatens to fall apart. Progress is intoxicating because the system lets you break it and then try and worm your way out of the thing you’ve broken, which draws attention to the inherent trappings of level design and encourages the player to usurp them.

Corrypt is really two games inside of one; it reveals that Brough’s idea of iteration is to make an established system more ridiculous and less predictable. This is not repetition. It is economical creativity. The thing that makes his puzzles brilliant looks something like an accident, a bug that didn’t get smoothed out, a premeditated glitchiness. The relatively innocent dungeon-crawler, Game Title, could only have been created so its deliberately broken version, Game Title: Lost Levels, could be conceived. The transition from playing Game Title to playing Lost Levels, which relies on mechanical exploitation of the former, is uncannily similar to the cranium-crushing dive Corrypt takes twenty-or-so minutes in.

While we’re on the subject of sequels or expansions or whatever, we would be remiss to shrug off Reverse Passage and Reverse Passage 2: Mother’s Edition as half-baked digs at that game where you walk in a straight line until you die. You know the one. It’s a METAPHOR for that thing we’re all trying to forget about when we play games (I’m kidding!). Reverse Passage beats Jason Rohrer at his own game, out-minimalizing Passage with less playtime, less variety, and zero movement animation. Reverse Passage suggests a clumsy lack of subtlety in the premise of games as Metaphors for Life.

Just when you think Brough has exhausted an idea, he’ll swoop in and hit you in the face with the weird version. In Reverse Passage 2: Mother’s Edition, you “catch babies” to “avoid the time paradox” and “hold Z to feel emotions.” No really. The emotions in this game aren’t some cheap trick (well, they are); they’re actually implemented as an input, a button that you press. This is an absolutely ridiculous thing to do, of course. Whenever you “feel emotions,” characters and backdrop bleed together, obstructing your vision. Said emotions have zero consequence in terms of quantifiable feedback, but they make the game more difficult and more interesting.

Let me explain: as you progress, and the speed of infants flying towards your womb becomes more difficult to manage, you have less time to feel emotions. Your “feelings” quite literally interrupt the game and make it difficult to focus on what’s important. But wait a second, what IS important? Catching babies? Avoiding the time paradox? Why should I dismiss arbitrary emotions for the sake of an arbitrary high score? Such lingering questions make the design philosophy of the Reverse Passage franchise difficult to pin down.

While we’re on the subject of games that are probably fucking with you, Number Quality relies on its disintegrating environment. Numbers are scattered on the screen, and you must collect them in order from zero to nine. The screen blurs at a rate that’s faster than you are, so it becomes necessary to memorize the position of each number. This game is hard, but its doppelganger, which reverses the design so that the screen gets clearer as you progress, is stupid hard. Ytiluaq Rebmun isn’t a symmetrical opposite in the strictest sense of the word because the numbers appear with clarity for a split second. You get a glimpse of a chance to try and memorize their positions before they become illegible. It’s an example of clumsy difficulty, which reminds us that any design can be molded into an exercise in futility.

Kompendium is an entire album of local two-player games that expects you to stop wallowing in perpetual, lonely, single-player melancholy.

Brough’s earlier two-player effort, Chaos Penguin, predicts Kompendium in its emphasis on strategy over speed. Chaos Penguin limits the importance of quickness through turn-based play and spell-casting that relies on percentages. Kompendium, however, is more interested in the tension between real-time and turn-based play, and it uses this tension to combat the tyrannical authority of twitch reflex.

Each title on Kompendium flirts with chaos without abandoning order, a balance which makes for moments of earnest tension. At first, the games feel more cooperative than competitive as you and your opponent both try to learn the rules and make sense of the controls. As the games become familiar, competition gets more heated. Most of the time pacing is frantic, and suspense builds in the rare moments in which you wait for something to happen.

Almost every game features a dash of randomization that complicates the notion of predictable outcome. Glitch Tank undermines twitch reaction by shuffling its controls, so that overzealous haste makes you your own worst enemy. Chang Chang, a brilliant, fast-paced distillation of Chess, allows both players to move one randomly selected piece as many tiles as possible within a time limit. Each piece has a range of attack, as it would in chess, and if a piece is caught within the opponent’s range at the end of a turn, it’s removed. Exuberant Struggle makes you fight over randomly placed resources to spawn turrets, tanks, and bombs.

Some of the games encourage you to accumulate territory by persisting with whichever strategy happens to be working at the time. In Ora Et Labora, standing on different tiles spawns different units, and it’s possible to spawn an entire forest of deadly trees, then instruct that forest to skulk menacingly towards your unfortunate opponent. Capricious Atom forces each player to dodge flurries of bullets to claim buildings that affect the trajectory and properties of said bullets. March Eternal spits out units and resources with little regard for which ones you want or where you want them; your job is to collect resources and periodically demolish your opponent’s front line with a single swift keystroke. Hostile Pantograph rewards creative risk-taking; each player draws a maze while traversing the maze that the opponent has drawn.

Twilight Beacon and Zeta Forge both ask players to shoot squares, big and small, across the screen in hopes of breaking the opponent’s line. They reward carefully timed alternating between charged attacks and flurries. They offer choices between offensive and defensive approaches, between quality and quantity, and both delineate these strategies with simple geometry.

Considered as a body of work, Kompendium‘s minimalist aesthetic creates tension through productive uncertainty.

Kompendium isn’t Brough’s only game album. The abstract, unfinished Idiolect seems to have influenced the design of later puzzles, in that it explores the illusory nature of environments as well as the assumptions that a player makes about visual artifacts. Such themes become important to how design functions in later works like Corrypt and Lost Levels. Idiolect also introduces an exhilarating feedback method, which involves layering a more structured musical interlude over an ambient backdrop when the player touches the correct object. This happens in Hyperabuse Monolith as well as You and Your Motion, and it feels like a fruitful area of Brough’s thinking that has yet to be fully explored.

The Sense of Connectedness is the most fully realized work in Idiolect. With its ambiguous response to the player and cryptic narrative interruptions, Sense remains partially incomprehensible through to the end. It imparts an uncomfortable sensation that permeates the entire album.

You and Your Motion takes some garbled prose and attaches it to floating limb sculptures that you click on. Fire Up The Lemma Engines is similar to the first La La Land game in that the difficultly lies in figuring out what’s going on as you’re obstructed by layers of visual noise: Where is my cursor? What am I doing? Should I blink? Accept the limitations of your own control and press onward. Conversely, Black Pyramid Script and Cryptoforest are tourist attractions: Look at the colors as black corridors open and close; move horizontally as your vision propels itself past neon trees.

This is the Dystopian Future asks you to redirect characters towards one another without letting them touch. A Simple Instruction twists in upon itself, as you affect its swirling patterns. In Cubic Computing Carcass, you glide through a space-maze of cubes in hopes of discovering keys to move forward. The Bristling Beard of Science is a nonsensical block puzzle that changes the score as you go. Knot-Pharmacard Subcondition J is explosive and thrilling, and I can’t really tell what’s going on. Noticing a pattern here? In Hyperabuse Monolith, your avatar doubles as mini-map; blue enemies pursue in frantic zigzags; red blocks ricochet. Excitement mounts. Everything multiplies. The screen fills.

If nothing else, Idiolect, in its ambiguity and visual experimentation, expresses an interest in scrutinizing existing assumptions about what makes good design. There’s a kind of beauty in projects that are allowed to remain unfinished.

There’s been a recent wave of “design purity” in games that don’t really need stories because they satisfy us with the sturdiness of their systems. Terry Cavanagh’s Super Hexagon comes to mind. I would say that Brough’s games fall into this camp. But while Hexagon asks its players to ritualize practice, twist their brains into unfamiliar shapes and develop a heightened responsiveness, Brough’s work encourages thoughtful deliberation.

One might be tempted to characterize his current visual style (which begins to distinguish itself in the tank exploration game, Ludoname) as a willingness to sacrifice aesthetic elegance for an elegance of design. Yet, there is something undeniably elegant about Brough’s brand of ugliness, an ugliness that is somehow pleasing to look at. Edge attributes this effect to a “pleasantly garish colour pallete.”

This ugliness is apt, since his games often employ a visual effect that looks like a glitch in order to surprise the player with a kind of revelation. Not all of Brough’s games, however, look like Game Title or Zaga 33. Babeltron 2010 is the most visually stunning typing game I’ve ever played; it presents you with an electrified tower of language and represents one of the few experiences in Brough’s portfolio that relies on visual flair.

Brough has also been known to dabble in cheeky thought experiments in the vein of Pippin Barr, and I heard you like videogames is one such experiment. It might be helpful to think of this game as one of those Russian doll things that you open up and there’s a smaller one inside, and it goes on forever: except videogames. Inside your computer screen there is another screen with which you can interact. Interacting allows you to move through this screen in which you will be presented with another screen and a handful of non-interactable objects. In this fashion, you may progress through infinite screens.

The only thing you can interact with is a videogame screen, yet doing so never allows you to do anything except this exact thing. The only reward is looking at static objects, like desks or shelves or trees, that randomly populate the margins of each level. The only verb you’re allowed is diving, deeper and deeper into a boring, meaningless rabbit hole.

Eventually, even the meaningless visual reward abandons you. Interacting with the screen creates a distinct sound, an encouraging beep. Once the screen is too small to see, you can keep playing forever by listening for the correct sound. When you get to this point, it doesn’t matter what the objects are anymore because you can’t see them; you’re just listening to beeps and pressing buttons. Congratulations, you have effectively reduced the game from almost nothing to even less of something. When you want to quit, you have to hit escape as many times as the number of screens you’ve passed through. How long you persevere is how long it takes to quit, so in a sense, you’re punished for persevering. I heard you like videogames is not so much a game as it is an endless reflection of what we do when we jump into another world just to escape the one we’re in.

Mysterious Sniper shares a similar attitude, though its tone is somewhat baffling. This game is funny because you’re supposed to be playing as a sniper, a character you would think generally operates on some level of premeditated expertise, but it’s disturbing because the sniper isn’t the only mysterious one, as the title suggests. Your target is also shrouded in mystery, presumably surrounded by innocent bystanders. The only way to get more information on your target is to kill something. After your first attempt, which is a wild guess that will probably be wrong, the game informs you that “the enemy is slow,” or “the enemy is short,” or “the enemy is blue.” Your potential target is narrowed, and you either get lucky or continue to knock off expendables. Mysterious Sniper scrutinizes the arbitrary goals we’re assigned when we play a game and asks how we might question or subvert those goals.

Zaga 33 is a rogue-like that chops off all statistical fluff, to an even greater extent than something like The Binding of Isaac. Enemies move in half-predictable patterns, and the player must choose to conserve items or use them quickly in order to figure out what they do. There’s hardly any fiction attached to Zaga 33, but its player-driven narrative benefits from the absence of an excess of numbers.

Cube Gallery is an interactive gallery in which the player tenuously participates. The environment shifts according to what you like looking at most, reminding us that there’s another kind of purity in mechanics-light design.

Even the titles that don’t work that well in practice have exuberance. Glutton Quest, a sidescroller that’s stupidly hard and nearly incomprehensible, is interesting because it’s interested in stupidity. Its narrative prose could have been pulled from Idiocracy, and you have to fight a giant teapot called “Chaos Kettle.” Movement is delightfully clumsy, and your secondary weapon is a magnetic rope that allows you to propel yourself across an entire level, frying enemies along the way. Smestorpod Infestation is a shmup that asks you to maintain a power grid as the screen scrolls upward. Deathlight is an absurd, creepy, frustrating Lovecraftian rowing simulation. Feline Feeling has intentionally unwieldy controls because, well, a mouse is difficult to catch, even if you’re a cat. Resistance Revolution is like Dyad with less drugs. Grand Vampire Chase has a really good chomping sound effect. What was I talking about?

Vesper.5 is more idea than game, yet this form makes the idea visible in such a way that feeds the imagination. What a simple premise: there’s one level, and you get one move per day. Vesper.5 suggests that we would appreciate games more if we weren’t allowed to play them whenever we want. On the one hand, this is a trick that can only work once. On the other hand, it’s a trick that games have already been performing, desperately, in commercial, free-to-play models.

Vesper.5 asks: What happens when the ability to play a game becomes its most important mechanic? What if all games were to allure us by restricting our access? Would we reward them by calling them Art? Or punish them by calling them Entertainment? In some sense, the implications of Vesper 5 strike me as eerily oppressive, as if I’m a child who needs structured limitations, yet limits are what games are made of.

In The Sound and the Fury, Quentin’s father gives his son a watch, calls it the mausoleum of all hope and desire and says: “I give it to you not that you may remember time, but that you might forget it now and then for a moment and not spend all your breath trying to conquer it.” Vesper.5 says I will take both more of your time and less of your time. Vesper.5 laughs at the prospect of additional hours because it operates not in hours, but in seconds, yet it also operates in days. Vesper.5 curls up even as it stretches, reminding us of our strained, dysfunctional relationship with time.

(Newer versions of Corrypt, Zaga 33, and Glitch Tank are available for purchase on iOS. O is a two-player touch-screen sport available for iPad.)